Djon Mundine OAM, curator, long-time activist, mentor, and deep thinker, has turned his hand to art. Self-confessed ‘occasional artist’, Mundine is a man of many talents, who has since the 80s adhered steadfastly to a recurring theme: that Aboriginal people be recognised—as First People in all their diversity, and as part of the Constitution.

He hails from a line of people with deep convictions: his maternal grandfather John Donavon, was an early active member of the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association, the first Indigenous political party formed in the 1920s. Along with Djon’s brothers Warren, past National President of the Labour Party, and Roy, who earlier this year was appointed Aboriginal Elder for the Australian Army, the Mundines have continued the same fight, albeit wearing different gloves. His sisters, Olive, Ann and Kaye Mundine, who held the position of Queensland Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission from 1988 to 1990, were all involved in the Aboriginal Medical Service and the land rights movement in NSW, indicating that a social conscience and regard for Aboriginal People is a family affair.

Every wall and every object in the room has been painted with wide brown stripes interchanged with white.

Returning to Auburn, the suburb where he spent his school years, Mundine has successfully, and literally, made his mark on the walls of Peacock Gallery—a small community-run space nestled quietly in the Auburn Botanical Gardens.

His exhibition Another Country focuses on Duck Creek—the small creek-cum-river that runs through the suburb towards the Parramatta River. In Mundine’s childhood, the creek was a dumping ground for toxic waste from the heavy industries of Newington Armory, the Clyde Refinery and a sprawling railhead; although before colonisation the creek had sustained the Burramattagal and Wategora people for thousands of years.

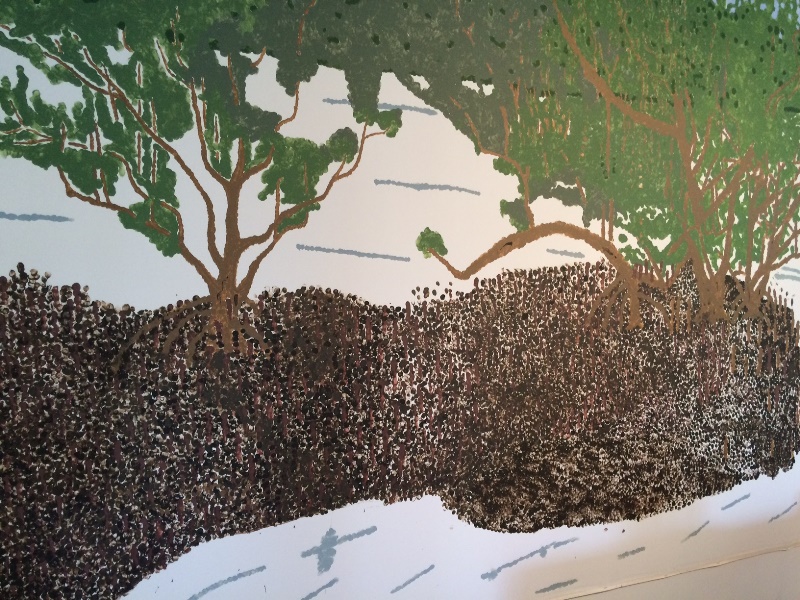

In Another Country, Mundine presents three pictorial views of the creek. The first is a wall mural painted in the western paradigm of landscape art, where the scene is ‘viewed’ passively from a vantage point. Using a rough pointillist technique he, and a number of local artists, painted the river bank in browns and greens. The water is left blank, devoid of paint; a sign that the crew, bored with the idea of completing such an imperial rendering of it, failed to engage with an outsider’s view of the creek. The absence of paint deftly conveys that being connected to country is critical for both people and the environment.

His second interpretation of Duck Creek, placed adjacent to the mural, is a short video showing the patterns of the water’s surface, formed by wind and current. It loops past the viewer and returns, and despite the glare and washed-out colour, the repetitive rhythm reminds us that the water is the life force of the creek.

But it is in the gallery space itself, that Mundine really makes his mark. Here, he strikes broadly and loudly. Every wall and every object in the room has been painted with wide brown stripes interchanged with white. These he says, are tide markings, the brown recalling the colour of the clay on the river bank, and the early industries of brickmaking and potteries established there.

This striped room, conjuring body paint and carved trees, best conveys the environmental aspect of Mundine’s message. Not only is he flagging that this deeply urbanised, multicultural suburb was once Someone Else’s Country, but by baptising it in the tide of the river, he signals that with the loss of Aboriginal custodianship came social degradation and environmental desecration.

It’s a message that quietly reminds us that while white fella made many mistakes way back when, in the repatriation of Country there is both political and social hope, and an opportunity for a greater environmental redemption.