Blair French explores how MAMA’s bold transformation set a new trajectory for the museum, shaping its identity, ambition, and community role. He reflects on the challenges, sustaining regional arts careers, and embracing experimentation in shaping the next decade.

I recall that when Murray Art Museum Albury opened 10 years ago, it was a very dramatic shift from the original Albury Regional Art Gallery, established in the early 1980s. Now that MAMA has just celebrated its 10th anniversary, do you think such a bold rebrand offered the organisation a new trajectory – and if so, how has that shaped the organisation to what it is today?

Yes, I think it did. I only witnessed that transformation at a distance, but even then, it was clear that MAMA was embarking on a new trajectory. Now looking back from inside the museum, I have the sense that both the city council and community more broadly saw the growth from a regional gallery into an art museum as a statement of civic ambition, both in terms of the services of a new museum to its community and in terms of an outward projection of the city’s identity. The attendant sense of confidence and ambition has been really important to MAMA’s subsequent activities and successes.

MAMA, as a particular branding, has also been important. It has a standalone recognition, but the full title – Murray Art Museum Albury – explicitly highlights the city’s connection to the broader Murray region. I think that outward perspective has been really critical to the evolution of the museum’s identity and confidence.

Further to the rebranding into MAMA, can you talk about how, or if, the permanent collection continues to underpin the organisation’s DNA?

The collection is critical. It dates back to 1947 with the establishment of the first Albury City Art Prize, so it is a lot older than the institution. It is central to MAMA’s existence.

With the Albury Regional Art Gallery opening in 1981 and focusing in on photography through the establishment of the National Photography Prize in 1983, the organisation identified a direction where it could build a collection of national importance with limited resources – a collection that institutions, audiences, artists and curators nationally would recognise and wish to engage with. That has been incredibly important to the direction of the museum, complemented by other collection priority areas such as work by First Nations and, in particular, Wiradjuri artists and work by artists of the region and or work speaking to experiences of this place.

We always have parts of the collection on display, usually in changing thematic displays. Right now, quite deliberately, all our galleries are dedicated to collection displays marking the moment of MAMA’s 10th birthday. We have deliberately stepped back ourselves and invited four guest curators to develop exhibitions: artist and curator Talia Smith; artist Haley Miller Baker; and two exhibitions curated by local residents. One is by a long-term volunteer and museum friend, Sally Denshire, who knows the institution intimately. Sally has created an exhibition looking at the evolution of the collection prior to MAMA’s establishment. The other is curated by Madeleine Steer, an alumni of our young artist ‘RAW’ program. Maddie grew up in Albury and is now studying curatorial practice at Monash University. These two exhibitions are fascinating for the ways they use the collection to convey particular experiences of this place. Their popularity highlights the connection the collection can have to the community and to audiences, both immediate and those visiting the region.

Where do you feel MAMA sits within the cultural eco-system, locally, state-wide and nationally?

MAMA’s vision is to be a regionally transformative and globally engaged art museum. So we look to work with real agency within our regional communities and through that to understand and convey how these communities of which we are a part are also connected to ideas, histories, experiences and other communities nationally and internationally.

Critical areas of active connection include our work with kids and families, providing opportunities for young people in particular to engage with creativity and culture from around the country and beyond – real opportunities to build confidence in thinking critically and acting creatively.

Another important area of active connection is through supporting artistic regional practice by providing development, presentation and employment opportunities for artists. In addition to exhibition and acquisition opportunities, we employ artists as tutors and present and sell the work of local craft artists and makers through the MAMA Store. We are trying to act as a hub that operates to the benefit of artists here in various ways, promotionally, professionally and financially.

Another other key aspect locally is working strongly with First Nations communities; developing opportunities for cultural activity and for that to find audiences through appropriate presentation models and community engagement.

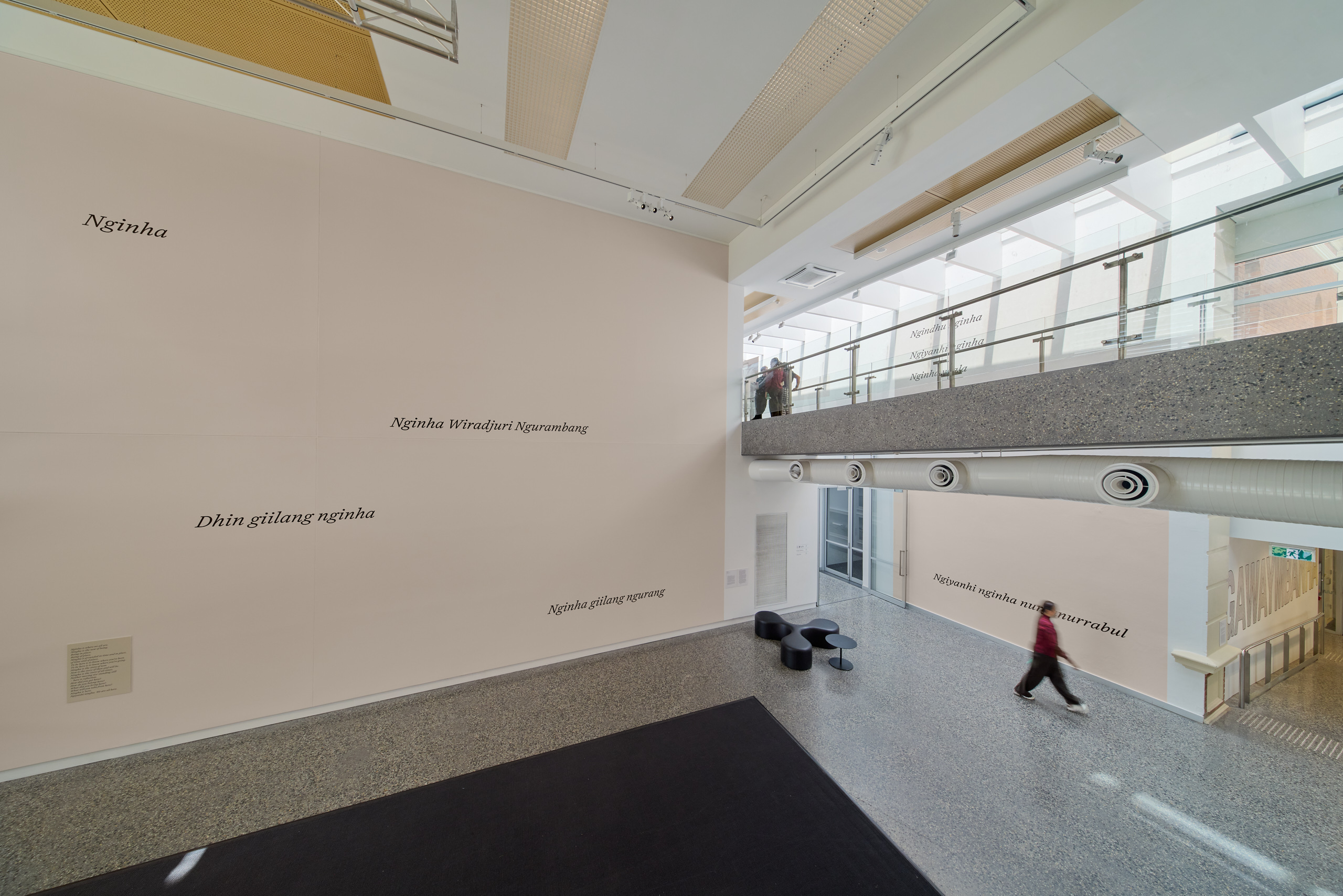

Nationally, we position ourselves as a place for artists to come and make new work, an opportunity for that major moment in an artist’s career. Our commissioning program and projects such as the National Photography Prize (NPP) are aimed at providing rich possibilities on a nationally significant scale for artists to stretch their work. The NPP is unique in being a prize project where selected artists are able to present significant bodies of work that truly highlight the breadth and complexity of their practice, and where MAMA meets artist participation costs in a manner commensurate to any of our exhibitions and provides exhibition fees. Our commissioning program is ongoing. We are currently showing major works by D Harding and Jeanine Leane, produced here. The third of our nginha seasons in the first half of 2026 centres on five further major artist commissions.

Looking ahead, what are the key opportunities and challenges for MAMA over the next five years?

For many years, the pressure to ‘relevance’ in contemporary art has weighed heavily on the public museum and gallery sector. The need to be constantly working at it and articulating it culturally, politically and within a community. But ‘relevance’ can be a dangerous word, depending on how it’s being deployed. I believe that the challenge – and opportunity – more broadly for the sector lies in highlighting the place of the art in forging enjoyment, understanding and evaluation of culture within the community. It’s that challenge to consistently create experiences for our public with art and artists and to highlight how art can and does help us understand how we live together, how we communicate and how the art museum can be a place to explore our civic responsibilities of being together.

Aligned to this is the challenge of keeping the grit in our work, so that we can be a place where art can ask the hard questions while making an engaging and safe welcoming space for audiences.

There is also the ongoing challenge of sustaining careers for artists, art workers, and creative communities in our region and beyond. It’s vital that we do that work over the coming years in partnership with others in the region and nationally. There is a leadership role for MAMA in that.

I’ve talked about challenges in terms of the civic and professional role of the art museum broadly. The big opportunities for MAMA specifically right now lie in building upon the work of our current nginha program and our concentration through it on the art of our region, the connection our communities feel to the collection and perhaps most notably of all in a regional context the evolution of our direct work with artists in commissioning relationships – we have a significant opportunity to build the significance of that program and to grow partnerships with peer organisations nationally and beyond through it.

What insights do you have for organisations that may be considering a dramatic shift in vision or focus?

You mentioned the word ‘bold’ at the outset, and this is important – you need to be bold and be confident in being bold. Be prepared to experiment. By which I mean you go through a certain extent of developing a vision or a change of direction, and you go through all the processes – including working with your teams and communities and consultation – but then it’s critical to be ready to try different things out within the framework you’d established. Don’t decide on and refuse to deviate from a singular path from the outset. Try things. Be prepared to fail and be prepared to change course. The contexts and environments in which we work and live change so quickly and dramatically. Sometimes it can take a year or two to get an idea in place, a structure around it, stakeholder commitment to it, or funding for it, by which time things might have changed. You might need to adjust that vision, tweak it or turn it around. Be confident, but don’t fear a process of testing, reflecting, shifting and adjusting.

Blair French is the CEO at Murray Art Museum Albury

Insights interview conducted by Brett Adlington, CEO, Museums & Galleries of NSW.

Insights is an interview series highlighting the voices of museum and gallery professionals across New South Wales. The series features conversations with individuals working at the forefront of the sector, demonstrating how their ideas, leadership and day-to-day practice contribute to a more vibrant, resilient and inclusive future for museums, galleries and Aboriginal cultural centres.

If you would like to participate in our Insights series, please get in contact.