At Object’s New Weave, the audience is treated to a view of an artistic landscape so varied and strewn with significance, it’s hard to know which pieces to examine more closely.

One of six exhibiting artists, Lorraine Connelly-Northey last week spent time in conversation with Indigenous artist Jonathan Jones. Much of what Connelly-Northey said was insightful–articulating the disconnect between the cellular, visceral drive to being an artist, her desire to respond physically in making things, and the role of an artist within the galleries and institutions who collect her work. Having never set foot inside a gallery until her work was collected by one, Connelly-Northey describes her creativeness as an intuitive response to stimuli rather than as deliberate decision about occupation or career.

She spoke of her influences, identifying Home as significant on several levels. Her luck or not, at being the daughter who was assigned the tasks of crocheting, craft and weaving; a strong obligation to a father who had himself a fondness for corrugated iron as material; her position as single mother residing in her parent’s home; and, palpably her deep connection to the land into which she was born–the Wamba Wamba and Wadi Wadi borderlands.

During the conversation, Jonathan Jones referred to Home country as the “tortured landscape” and described it as carved up and fenced; stripped bare, cultivated; forced to perform, produce and support industry, agriculture and a myriad of activity. So it came somewhat as surprise that the depth of Connelly-Northey’s sense of belonging overrode all this, that the depth of her connection to Home means she responds to country as modern day hunter and gatherer.

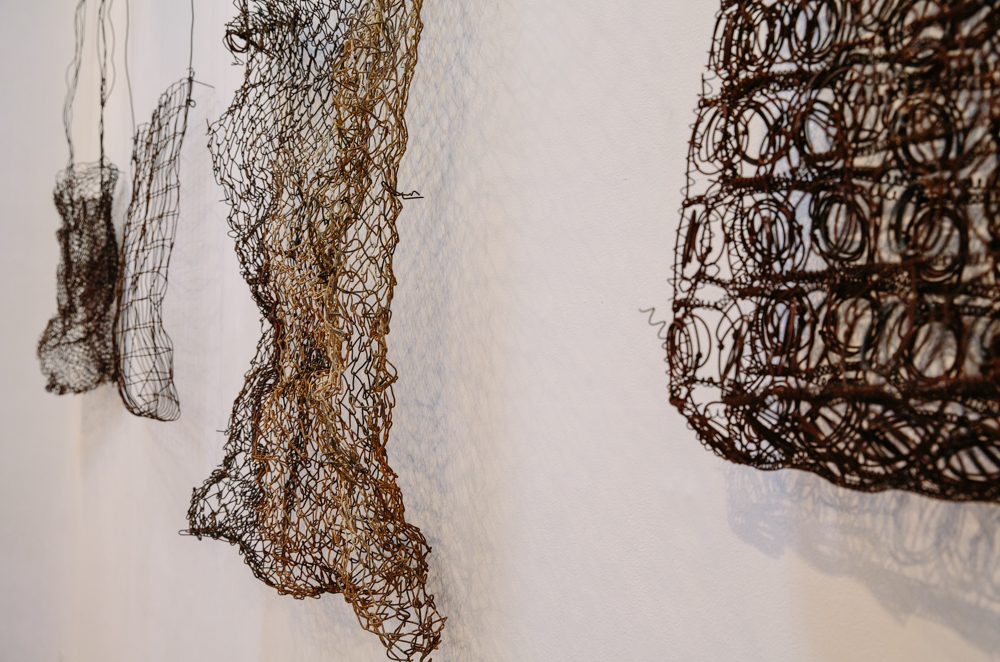

They’re made of things found: rusty mattress base–all exposed spring and wire coils popping; steel re-bar, old corrugated iron and rolls of fencing wire.

It’s a striking notion, given more impact when viewing the collection of Narrbongs in the New Weave exhibition. Traditional woven string bags are sculpted into over-sized pieces. They’re made of things found: rusty mattress base, exposed spring and wire coils popping; steel re-bar, old corrugated iron and rolls of fencing wire. Picture the hauling, the dragging and the hoisting of this discarded, unwanted material–rubbish in anyone else’s eyes–onto a trailer. Picture the physical energy expended as they are hand cut and rendered usable by wire cutters, hammer and heat. It’s an entirely unromantic image, yet pressingly evocative and one that sits boldly beside conversations of totem and language groups and rejuvenation of traditional cultural practices.

Lorraine Connelly-Northey’s pieces loom large and beautiful. She knows how to make a statement, using scale as her ally, she draws your attention to intricacy born out of industrial and to the contemporary wrought from traditional. Her work is more ‘woven’ than it at first appears–woven from a deep connection to country, respect for land and poignantly, the wiry, tenacious and unbreakable emotional bonds to her people, their continued existence and to the land where she belongs.

Editor’s note: Lorraine Connelly-Northey is the granddaughter of artist Alfred ‘Knocker’ Williams and prefers to use his spelling of Waradgeri as opposed to other spellings such as Wiradjuri, Wiraduri or Werogery.

She also uses the spelling of Wamba Wamba and Wadi Wadi, the alternative spellings of which are Wembi Wembi and Wati Wati and defines the area around Swan Hill in north-west Victoria.

Connelly-Northey has ‘walked’ her country and reminds readers that Waradgery lands comprise nearly a third of NSW.

View Lorraine Connelly-Northey’s Home country on the Indigenous language map.