White Rabbit Gallery, with its provocative collection of contemporary Chinese art and slick gallery space, never fails to be a visual treat. Presenting two exhibitions each year, we eagerly hopped into the first show of the year: Reformation.

Immediately drawn to the 37 canvasses spanning from floor to ceiling, three storeys high and tightly tiled together, the layout flags China’s collectivist disposition – at first glance cooperative clutter, on closer inspection, the paintings by different artists contain unique messages in varied styles; cartoon-like political narratives, traditional landscape brush paintings, textile collages and textural contemporary works. Like individual soldiers braced together in a united front, this opening wall sets the scene for the exhibition.

The notion of ‘taking a second look’ reoccurs with visual deception deftly used to disguise the serious themes of the show; censorship, independence, capitalism, power and identity.

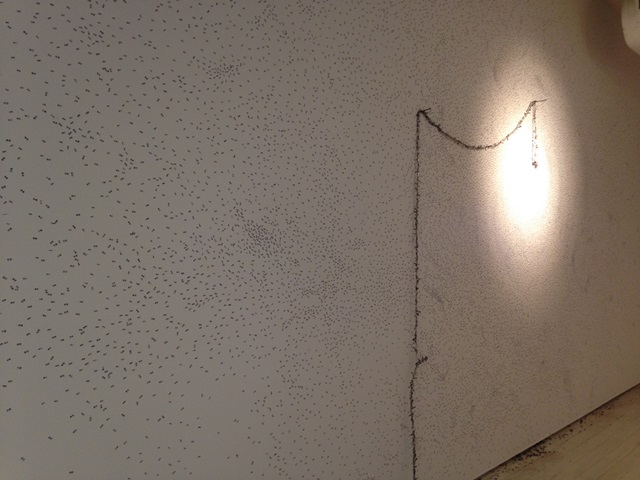

Zhou Zixi’s work found on the first level addresses the restriction of free speech and how events are erased from our memory when speaking about them or recounting them is forbidden. The canvas, washed out and foggy, forces viewers to squint to discern barely visible forms depicting the Tiananmen Square massacre. Propaganda as political tool is examined by Wang Zhiyuan in Close to the Warm; a stunning installation of hundreds of government-approved words scattered around a glowing lamp, fluttering like moths to a flame.

The notion of ‘taking a second look’ reoccurs with visual deception deftly used to disguise the serious themes of the show; censorship, independence, capitalism, power and identity.

Censorship is dealt with playfully on the upstairs level where motion detectors blur the images in a sex education video when walking within viewing distance. You can’t go past the MadeIn Company’s jumping castle for adults, made entirely from leather, whips, chains and BDSM accessories.

Trickery is at play again on level three, laid out to evoke a traditional museum exhibit with its carefully selected works and theatrical lighting. But here, nothing is as it seems. Objects from still life paintings are excised and hung on pegs; fruits and flowers on curling canvas pieces strung up like drying laundry. The subtext is one of latent violence, public exposure and fear.

Opposite that are Tu Wei-Cheng’s fascinating machines of dark wood and tarnished brass that look like antique magic lanterns projecting old black and white Chinese opera footage. The machines are in fact newly constructed devices made from found wood and household scraps and with this realisation we are forced to re-examine our sense of sacredness with which we view the past.

Reformation is on exhibition at White Rabbit Gallery until 3 August 2014.