Mervyn Bishop is foremost a storyteller. Spurred on by a local Brewarrina amateur photographer and his mother’s passion for photography, Mervyn Bishop became enthralled by the techniques and process of photography.

By the age of eighteen, the Brewarrina local was the first Aboriginal press photographer and beginning of a career that would span some of the country’s most prolific photojournalism to realist portraiture.

Bishop learnt “photography in the school of hard knocks . . .learning how to get the picture the editor wanted”. One of Bishop’s most iconic press images captured a nun carrying a terrified child in her arms outside St Margaret’s Hospital in Darlinghurst.

The front page shot titled ‘Life and death Dash’ won Bishop the 1971 News Photographer of the Year award. Bishop had deftly distilled a moment of maternal panic after the boy’s mother suspected the child had accidently overdosed on prescription drugs.

A testament to Bishop’s skill many opinion shapers of the day read in complex layers of colonial paternalism, race relations and religious institution involvement in Stolen Generations despite the boy being a non-Aboriginal Australian.

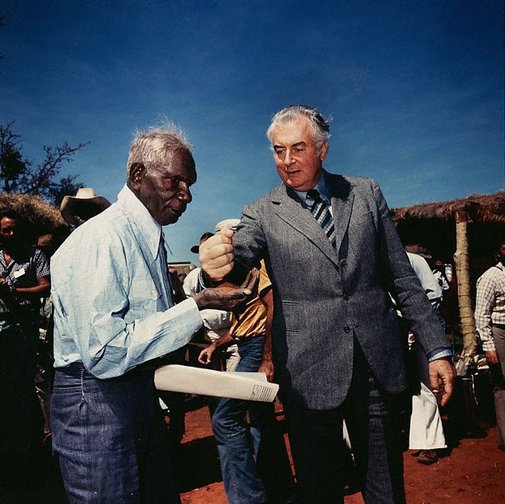

By 1975 Bishop was working for the Department of Aboriginal Affairs. The role enabled Bishop to document a period of rising advocacy for Aboriginal self determination and land rights. Bishop was at Wave Hill Station in the Northern Territory when then Prime Minister Gough Whitlam handed back land to Gurindji elder and traditional landowner, Vincent Lingiari.

The emotive scene that has come to represent a watershed moment in the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal relationship had initially occurred in the shade of nearby shed. Bishop asked the leaders to recreate the handover, the pouring of the red earth into Lingari’s hands, under the blue sky. Bishop’s sense of story and history infuse the iconic scene with an unmistakable sense of place and occasion.

In 1988 the NSW Department of Housing commissioned Bishop to document Aboriginal living conditions throughout the state. Not content with a clinical and dispassionate recording of dilapidated houses and unmaintained state assets, Bishop produced a photographic series that conveyed the strength and resilience of Aboriginal communities surviving through living standards that should have been unacceptable for the time and age.

The Burnt Bridge series taken in south Kempsey on the NSW coast possess a lyrical realism that shows the gravity of living conditions without objectifying its subjects or stripping them of their dignity. ‘Woman standing near electric power cord in water, Burnt Bridge’ is not framed to subjectify poverty opting to instead show a multilayered image of resilience, hardship and brutal realism.

Through his success as a photographer and storyteller Bishop notes that he hasn’t necessarily had the time to reflect upon impact his photography has had on capturing iconic moments in history and the stories of Aboriginal communities. Bishop told the National Gallery of Australia, “I was too busy working to have time to stop and think about how photography related to myself, my family and, specifically to the Aboriginal communities I photographed. My relatively recent involvement in education has led me to want to understand much more about how photography relates to my own life and history.”

Bishop’s work is held in the collections of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, The Australian National Maritime Museum and The National Gallery of Australia.