The Island | Artwork & Artist

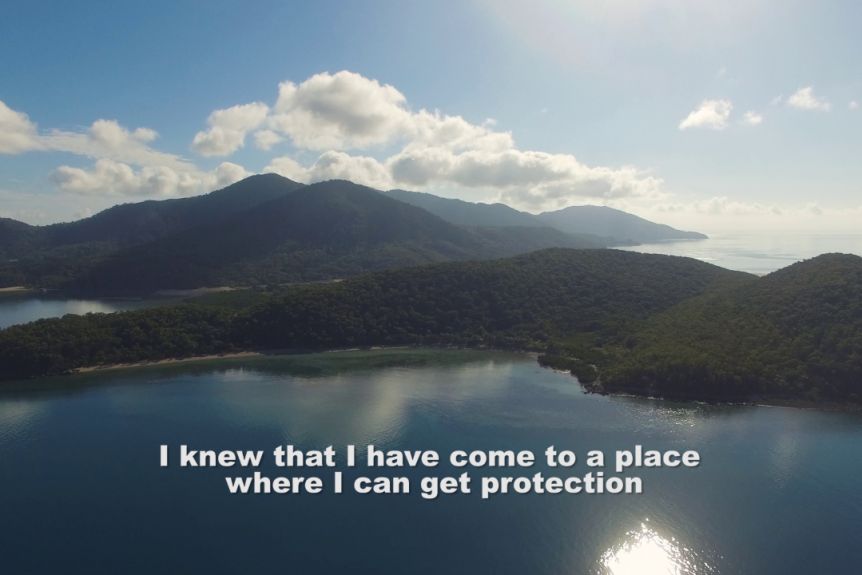

The Island, 2018 (still). Three channel digital video, colour, stereo sound 10:16 minutes Commissioned by Griffith University Art Museum, 2018.

A powerful survey exhibition of Aboriginal artist Vernon Ah Kee’s videos and wall texts, questions the frameworks of power and role of language in embedded racism.

– Gina Fairley, ArtsHub

VIDEO AND INSTALLATION

The Island is the largest exhibition to date of Vernon Ah Kee’s video practice, juxtaposing these pivotal works with corresponding painting, drawing, vinyl graphics and installation.

whitefellanormal/blackfellame, 2004, single channel digital video, 4:3, SD video

00:30 seconds

In whitefellanormal/blackfellame (2004) Ah Kee introduces text into the video, asserting his political voice and exploring definitions of an Australian identity embedded within power relationships. In this exhibition, Ah Kee re-visits this work with a large-scale vinyl text installation drawing from the original video work.

“If you wish to insert yourself into the Black man’s world, with his history, in his colour, and on the level at which you currently perceive him, then know that you will never be anything more than mediocre. You will not be able to involve yourself in the decision-making processes of this land, and you will not have any constructive access to the social and political mechanisms of this land. At times this land will shake your understanding of the world, and confusion will eat away at your sense of humanity, but at least you will feel normal.”

tall man, 2010, four channel digital video, colour, stereo sound

11:07 minutes

fill me, 2009, gloss red vinyl

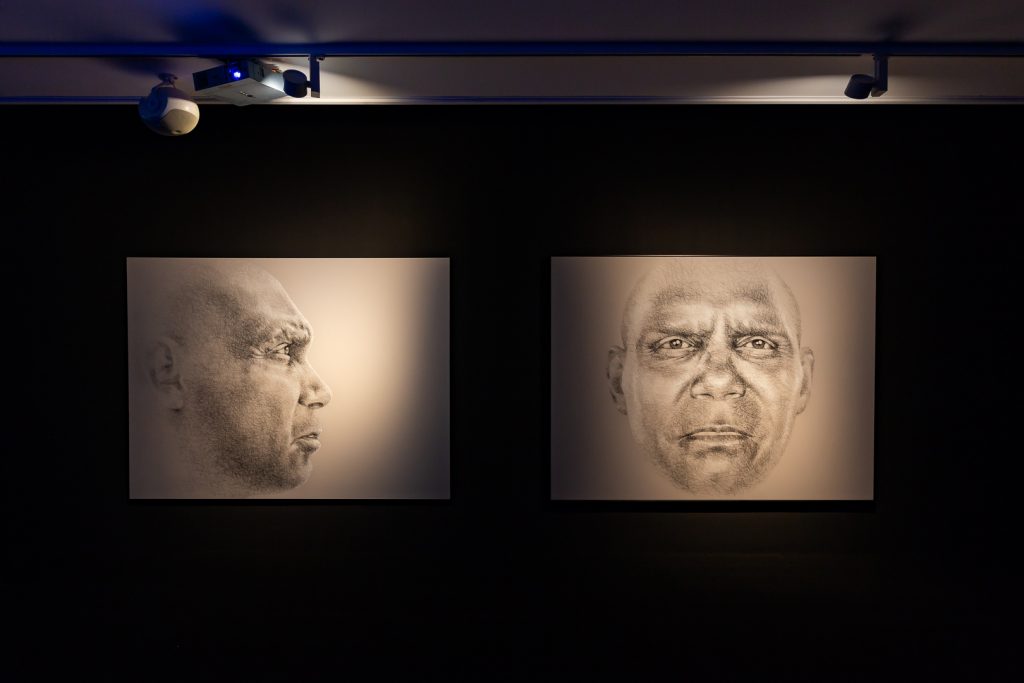

Lex Wotton (profile), 2012 , charcoal and acrylic on canvas

180cm x 240cm

tall man, 2011, charcoal, crayon and acrylic on linen

180cm x 240cm

The acclaimed document-style video work, tall man (installation image below) consists of a four-screen video installation detailing a crisis in race relations on Palm Island – an Aboriginal community off the coast of Far North Queensland. Presented beside two portrait drawings of Lex Wotton and a new vinyl text work, this video installation is the most comprehensive installation of tall man to date.

“My family has a history on Palm Island and in my family there are many stories about life on ‘Palm’. It is a place that means something to me.

Events of this past decade in Australia have changed the way we perceive beach communities like Palm, and indeed the Beach in Australia. ‘Palm Island’ is a word that means something more to me now, more than the island life that my cousins live there, more than the ‘place’ where my mother was born. In Queensland especially, when we say ‘Palm Island’, there are connotations that fix us, that give us pause and send our emotions racing toward tipping points. Like when we say ‘Cronulla’.

Lex Wotton, now intrinsically linked to the fire and burning buildings, his people’s frustrations, their pain and anger, that day so painted with his face and physicality. And whether he desires it or not, he is considered a hero by many fellow Palm Islanders for standing tall and speaking out so strongly. But he is regarded also for his grace in accepting the State’s pursuit and persecution that in the end became so focused on him.

While tall man is an idea of Lex Wotton’s involvement in the riot, it is also about the people of Palm Island and the circumstances in which they live their lives. It is about the lives of Aboriginal people and the way we see ourselves in times of this kind of trouble. As a people, the Aborigine in Australia exists in a world where our place is always prescribed for us and we are always in jeopardy. It is a context that we are continually having to survive. It is a context upon which we are continually having to build and re-build.”

Watch an ABC News report about Vernon Ah Kee’s Tall Man from 2010:

kick the dust, 2019, three channel video, colour, stereo sound

05:59 minutes

scratch the surface (riot shields), 2019, acrylic riot shields, charcoal

Dimensions variable

Ah Kee expands on existing themes in a new video and installation work, kick the dust (stills below) and scratch the surface (2019) respectively. Both works reflect on racially motivated violence in Australia and the disparity in justice, through a multi-channel video installation and a number of riot shields that are drawn upon with charcoal.

scratch the surface (riot shields) (pictured below) captures how the machinery of law utilises the police as its chief weapon for Aboriginal persecution—rather than protection. The shields represent the frictions and tensions in Australia, with the shield being a symbol of where these tensions meet: in protest and riots, a sheet of plastic acts as a threshold. The riot shields become a symbol of racial violence in Australia and the disparity in justice.

The shield is an object of control and suppression, not care and support. Charcoal lines mark the scars of these tensions and injustices. The new work, scratch the surface (riot shields), emphasises this, with charcoal drawn upon the scratched surface of the shields.

Vernon Ah Kee, scratch the surface (riot shields), 2019 Installation view, Vernon Ah Kee – The Island, Campbelltown Arts Centre, 2020

The Island, 2018, three channel digital video, colour, stereo sound

10:16 minutes (Installation view below)

we remember fear, 2018, gloss black vinyl

340cm x 200cm

survive the ocean, 2018, gloss red vinyl

340cm x 200cm (Installation view below)

Commissioned by Griffith University Art Museum, The Island (2018) is the second major multi-channel video installation continuing Ah Kee’s interest in the narratives of brutalisation and dehumanisation between island prisons and Australia’s colonial history. Responding to the history of the romantic and exoticised idea of ‘the island’ the work pits very personal asylum testimony with footage of Palm Island, a site plagued with a checkered colonial history. the island draws a line from current immigration policies to the Queensland missions and reserves of the 1920s and 1930s as well as the protectionism act that perforated this era.

As Ah Kee explains: “As I reflect on what is happening today, I cannot escape the idea that Palm Island is the prototype for Nauru, Manus or Christmas Islands. I am unwilling, or unable, to separate my own history with what is happening in those places. The history of the treatment of Aboriginal people is now being visited upon the wretched and the desperate cast-offs from global upheaval in which this nation is complicit.”

For me, it's fairly obvious the parallel between Manus and Nauru and Palm Island, being island communities and places of hopeless confinement...Plus, the cruel processing systems that they have in place.

– Vernon Ah Kee

Vernon Ah Kee, Belief Suspension, 2007-2009. Installation view, Vernon Ah Kee – The Island, Campbelltown Arts Centre, 2020

Single channel digital video, colour, stereo sound. Director and Editor Suzanne Howard. Sound David M Thomas. Regards David M Thomas. Photo: Document Photography

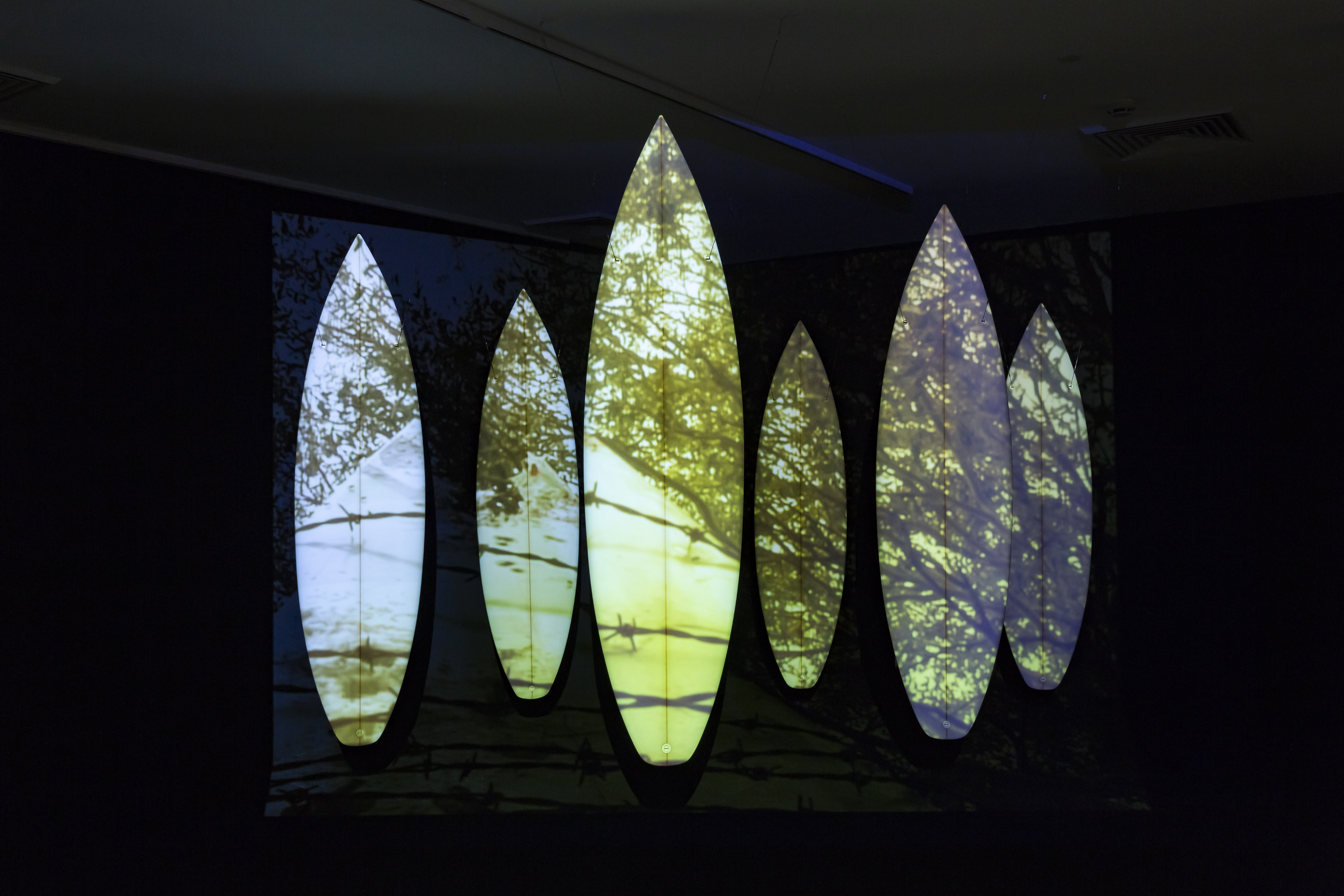

Belief Suspension, 2007-2009, single channel digital video, colour, stereo sound, surfboards

04:47 minutes

cantchant (series), 2009, digital prints

76cm x 136cm each

In Belief Suspension, 2007-2009 and Cantchant (series), Ah Kee challenges and reframes the power and privilege embedded in the contemporary Australian notion of the beach.

In Belief Suspension, 2007-2009 and Cantchant (series), Ah Kee challenges and reframes the power and privilege embedded in the contemporary Australian notion of the beach.

While it is Aboriginal people who truly embody the Beach, along with the whole of the ‘Australian’ land mass, it is White people in Australia who have established the Beach, particularly the East Coast, as a bastion of power and privilege; a territorial preserve for the White Australian ideal. And when it is threatened, as the 2005 race riots at Cronulla Beach definitively demonstrated, the base racism at the core of Australian society, at the core of Australian values, wheels into motion.

The surfboard and surfing lifestyle have become synonymous with the Beach and Beach Culture in Australia. In cantchant, the shield boards and their association with Aboriginal men, encompassed in the surfboards and in the video, are an exercise in reiteration; of identity, and of social and political positioning. Equally clear, is the all too real sense that the Black men, despite their colourful beach-branded apparel and flashy boards, do not fit.

Ah Kee discusses the cantchant series in this National Gallery of Canada Artist Interview:

lullaby, 2019, six channel 4K digital video, colour, stereo sound

11.30 minutes

Produced in 2019, the multi-channel video installation, lullaby directly references 2019 as the International Year of Indigenous Languages. The subjects include a mother and her young child speaking Farsi, reciting words and phrases of poetry and song. With minimal subtitles, language is extended beyond the spoken word, drawing attention to physical gestures of the body. Ah Kee decided to use Farsi as he believes, it is “probably the most loaded language in this country right now because of Australia’s immigration policies and racism against the Muslim community.”

Through the movement of the body specifically, this work portrays a life drawing in motion. It captures the essence of a parent passing on a language to their child wholeheartedly – utilising every tool necessary, physically and physiologically. It encapsulates the rich, layered and committed process of communicating ideologies that are handed from generation to generation.

Vernon Ah Kee, Lullaby, 2019 - Installation view, Vernon Ah Kee – The Island, Campbelltown Arts Centre, 2020

six channel 4K digital video, colour, stereo sound, 11:30 minutes. Commissioned by Campbelltown Arts Centre. Photo: Document Photography

TEXT BASED WORK

Vernon Ah Kee has been influenced by the text art of Barbara Kruger, the civil-rights writings of Malcolm X and James Baldwin and the poetry and art of the late Wiradjuri and Kamilaroi activist Kevin Gilbert.

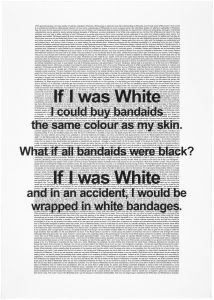

if I was white, 2002 – Series of 30 inkjet prints

if I was white is the earliest work by Vernon Ah Kee in The Island and encapsulates the silenced agony of living under everyday racial hegemony. The words on each of the 30 panels draw attention to a personal experience of ongoing systemic discrimination and racial privilege in Australia. Simultaneously, the words encourage empathy and change through action.

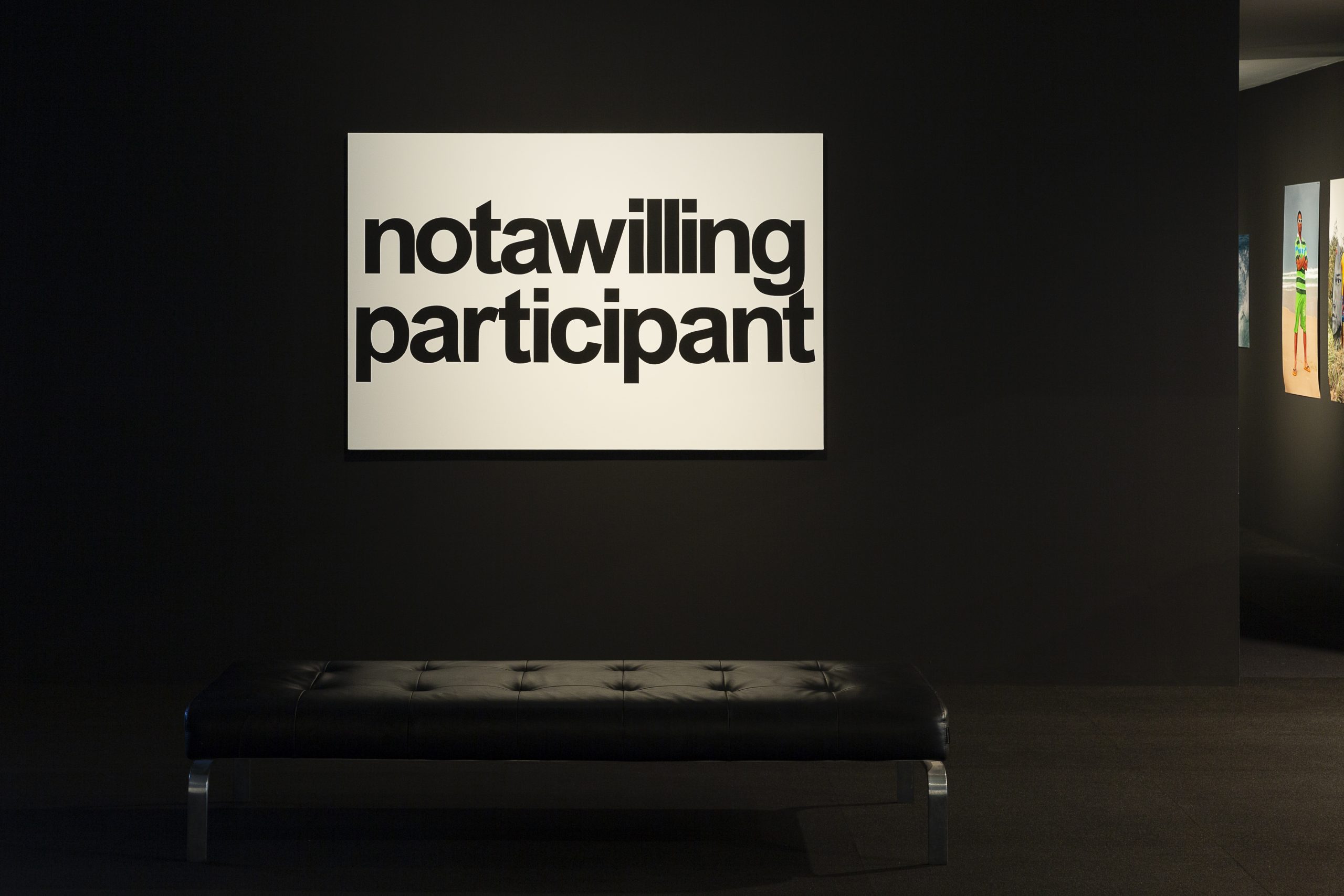

notawillingparticipant, 2007-2009 – Acrylic on canvas

From the earliest days of his career as an artist, Vernon Ah Kee has used text to explore and expose contemporary and controversial issues, surrounding the construction of race and systems of privilege. As the artist states much of his work evolves out of the “experiences of my mother or my grandmother on Palm Island and growing up poor and hungry and seeing privilege played out in front of me”. The use of bold, sans serif text also extrapolates Ah Kee’s desire to state his position plainly, in ‘black and white’, drawing on the slogans and placards of activist politics. Further, the artist’s technique of running words together compels the viewer to engage with the work actively in deciphering and, often, speaking the message

Installation view, Vernon Ah Kee – The Island, Campbelltown Arts Centre, 2020

Vernon Ah Kee, notawillingparticipant, 2007-2009

Wall vinyls

Ah Kee uses text in the medium of glossy or contrasting wall vinyls as stand alone artworks and in response to his video and installation works throughout this exhibition.

My work is Aboriginal art. It describes the life and history of Aboriginal people in this country. It describes the life of Aboriginal people in contemporary and modern terms. We are not Stone Age people

– Vernon Ah Kee

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Vernon Ah Kee was born 1967 in Innisfail, North Queensland, and lives and works in Brisbane. He is of the Kuku Yalandji, Waanji, Yidinji, Koko Berrin and Gugu Yimithirr people. Ah Kee was born just before the 1967 referendum that allowed the Australian public to vote whether to include Aborigines as ‘citizens’ of Australia.

Vernon Ah Kee’s conceptual text pieces, videos, photographs and drawings form a critique of Australian culture from the perspective of the Aboriginal experience of contemporary life. Ah Kee’s works respond to the history of the romantic and exoticised portraiture of ‘primitives’, and effectively reposition the Aboriginal in Australia from an ‘othered thing’, anchored in museum and scientific records, to a contemporary people inhabiting real and current spaces and time.

Ah Kee’s work has been exhibited in a number of significant national and international exhibitions, including Revolutions: Forms that turn, the 16th Biennale of Sydney (2008); Once Removed, Australian Pavilion, Venice Biennale (2009); Ideas of Barack, National Gallery of Victoria (2011); Tall Man, Gertrude Contemporary (2011); Everything Falls Apart, Artspace Sydney (2012); unDisclosed: 2nd National Indigenous Art Triennial, National Gallery of Australia (2012); My Country: I Still Call Australia Home, Queensland Art Gallery/Gallery of Modern Art (2013); and Sakahàn: International Indigenous Art, National Gallery of Canada (2013).

In 2015, Ah Kee was invited by curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev to present a new body of work as part of SALTWATER: A Theory of Thought Forms, the 14th Istanbul Biennial and participated in a series of significant public programs as part of the opening weekend of the exhibition.

Other recent exhibitions include cantchant, Art Gallery of Alberta, Alberta, Canada (2019), Boundary Lines, Griffith University Art Museum, Brisbane (2018), Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Divided Worlds, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide (2018), Will I Live, Apartment der Kunst, Munich, Germany (2017), Imaginary Accord, Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane (2015); GOMA Q, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane (2015); When Silence Falls, Art Gallery of New South Wales (2015-16); Encounters, National Museum of Australia (2015-16); Brutal Truths, Griffith University Art Gallery (2015-16); and Everywhen: The Eternal Present in Indigenous Art from Australia, Harvard Art Museums (2016).

Ah Kee’s work is held in a number of private and public collections in Australia and overseas, including the Sprengel Museum Hannover, Germany; National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth; and Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane.

Vernon Ah Kee was a key member in the establishment of Queensland’s leading Indigenous arts collective, proppaNOW.

A Campbelltown Arts Centre exhibition presented nationally by Museums & Galleries of NSW