Last week staff from M&G played round-a-bout at the Museums Australia Conference, ducking in and out of sessions, passing tickets from person to person and reaping the benefit of everything that was being talked about.

Here are a few highlights from those who attended.

Tamara Lavrencic, Museum Programs and Collections Manager

A definite highlight for me was Lindsay Farrell’s presentation on social inclusion through art and museums. His paper reported on a research project with homeless and marginalised groups in Brisbane. One program run over 12 weeks involved homeless people visiting The Australian Catholic University art collection and the Queensland Art Gallery/GOMA. At the end of the program each participant gives a presentation about a particular artwork. Farrell showed an image of a homeless man standing in front of a 17th Century Dutch painting. The contrast between his poverty and the almost gluttonous display of food was marked.

Samantha Hamilton, a conservator with Museum Victoria gave an illuminating paper on a collaboration initiated with Gupapuyngu clan Elders from Arnhem Land in 2011. The project aimed to involve traditional owners in the decision making process about conservation treatment options for bark paintings in the Donald Thomas collection. Initial discussions with Jo, a Gupapuyna Elder indicated that Western concepts of preservation were foreign to them; deteriorated barks were normally buried and replaced by new ones.

Samantha made a film for the community explaining each treatment option for the bark, which was translated into their own language by Jo. This helped broker trust between Samantha and the Gupapuyna clan, who had initially expressed reluctance for a female conservator to work with the bark, along with their preference for a Gupapuyna man to repaint it with white pigments. Through this process the community decided that Samantha had the appropriate skills to clean the barks, consolidate the flaking paint and support the bark by applying an aluminium splint.

Madeleine Brady, Gallery Programs and Touring Exhibitions Coordinator

Xerxes Mazda, Deputy Director, Engagement at Royal Ontario Museum, was a clear highlight for me with his keynote presentation addressing the need for museums to construct powerful narratives.

By utilising the basic principles of the dramatic arc, Mazda proposes that museums can create a full sensory experience, allowing viewers to connect with exhibitions and ultimately lose themselves in the narrative.

The dramatic arc is a simple device behind all successful Hollywood films and consists of five parts: the exposition, rising action, climax, falling action and finally, the denouement, or ‘resolution’ for those of us with unconvincing French accents. Mazda argues that we need to actively address each of these stages during exhibition development.

When considering the flow of an exhibition, the interpretive materials, object placement and audience interaction, museums should be constantly assessing an exhibition against the criteria of the dramatic arc.

Mazda also stresses the need to interlink each stage of an exhibition with a cause-and-effect relationship. Museums need to ensure that viewers are being drawn from one object to the next, and consequently through the entire exhibition. Mazda quoted the British novelist, E.M Forster, stating, “The king died and then the queen died is a story. The king died, and then queen died of grief is a plot.”

The beauty of Mazda’s keynote presentation was the pure simplicity of the concepts presented. And while it was ultimately aimed at museum exhibitions, I found it particularly interesting to consider how the power of the narrative could be applied to contemporary gallery exhibitions. Mazda challenged the audience to harness the universal concepts of storytelling in exhibition development and I will most certainly be taking him up on the challenge.

Steve Miller, Aboriginal Sector Programs Manager

The Indigenous Reconciliation session began with a reminder of a recommendation from the previous conference: that Indigenous people should be considered as foundational rather than a special interest group of Museums Australia.

It ended with a recommendation for an audit and evaluation of the level of engagement of Australian Indigenous people in museums and galleries. This followed earlier discussion around the uncertainty of the true impact of MA’s long standing policy Continuous Cultures, Ongoing Responsibilities, now a decade old.

Peter White, Senior Manager Indigenous Connections & Programs of the National Sound & Film Archive, did a great job chairing the session which was dense and diverse in its discussions.

Nancia Guivarra, Head of Communications with the National Centre for Indigenous Excellence opened the session by linking notions of excellence to Reconciliation. Genevieve Grieves reiterated the points from her earlier presentations about deep listening, cultural diplomacy, inter cultural work and generational vision. She also said that museums as institutions often don’t follow cultural protocols which causes tension when working with communities. The burden of this often fell on Indigenous staff.

Frank Howarth, speaking from the floor, said smaller museums were still afraid of making mistakes when presenting Australian Indigenous cultures and needed to stop ‘walking on eggshells’. The audience reflected that a similar situation exists with Indigenous staff in major institutions who are equally afraid of making mistakes; that the building of trust took considerable time; and that one Indigenous worker per institution was not enough. Indigenous staff often wanted to work with remote communities in their state which did not necessarily translate into the desired exhibition outcomes for institutions.

Dr Robin Hirst, Melbourne Museum’s Director of Collections, Research and Exhibitions, suggested imagining what we’d like to see in ten years’ time. I replied that 10 years was a worthy objective but in a history of 40,000 plus years, it was not very long. I was concerned about the ‘thought bubble’ discussion when the industry is retracting – regional Aboriginal cultural centres in NSW are closing – which raises questions about how the sector can develop greater depth of Indigenous engagement. It would be good to think beyond conventional exhibitions and public programs, to create a long term legacy reaching into communities and involving them in development including technical skills, as our own Travelling Places program seeks to do.

The suggestion to audit the entire museums and galleries industry arose early in the discussion but it was Margo Neale, Principle Indigenous Advisor to the Director at the National Museum, who moved it as a recommendation. With this adopted, the session drew to a close. It was encouraging to see that the audience of more than 50 people felt the discussion significant enough that nearly all stayed until well past the 5pm listed finish.

Michael Rolfe, CEO M&G NSW

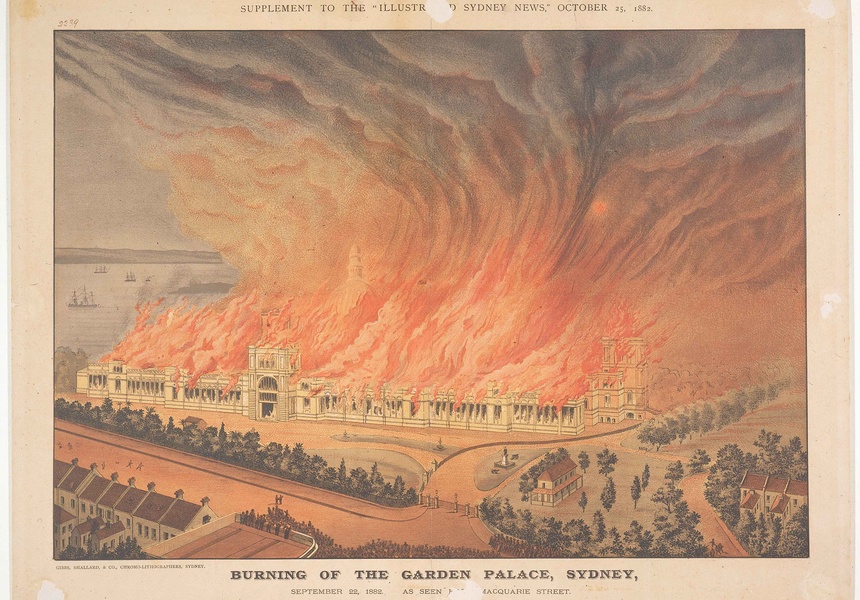

Burning of the Garden Palace

The months leading up to the conference saw various industry players calling for the establishment of a new and separate Public Galleries peak body. The jury is still out on this one, with a meeting planned for early August to further the debate. In the NSW public gallery and visual arts sector there is a belief that Museums Australia has, over time, dropped the ball in support and representation of the visual arts. To rectify this, a name change to ‘Museums & Galleries Australia’ has been proposed, however many think that it’s the organisation’s personality and governance structure that needs addressing. Time will tell.

Visual arts and gallery practice achieved a higher profile at this conference with Jonathon Jones’s enthralling opening keynote setting the scene for inclusiveness and consideration of big ideas. Jones, a Wiradjuri man, articulated the landscape as museum, and country as archive.

His work reconnects audiences with Aboriginal perspectives and histories. As the winner of Your Very Good Idea with Kaldor Public Art Projects, Jones has proposed a large-scale project, Barrangal dyara (skin and bones), re-imagining the historic Garden Palace in Sydney’s Botanic Gardens. The Garden Palace was destroyed by fire in 1882 along with the Australian Museum’s ethnographic collection; a loss to past, present and future generations.

In continuing the conference’s part focus on Indigenous programming, final speaker Genevieve Grieves reminded us to include Indigenous people as audience, rather than the subjects of exhibitions.

Of course there was more. Curator Bec Dean led a panel discussion about the impact interdisciplinary practice is having in our museums and galleries. Lisa Havilah, Director of Carriageworks summed the situation up nicely in highlighting that younger audiences were ahead of the game, “they seek to engage with ideas that are not limited to practice”.

In the end, I’m drawn back to Kim Williams address on the final afternoon. His clarion call for “curiosity, creativity and learning to be at the centre of all we do” is a signature quote for all to take home, because as he said, “there is no future in being bland”.

It was great to have an opportunity to work with Museums Australia (MA) on the presentation of their 2015 national conference. With just on 450 delegates and a vibe that seemed to purr success, highlights were many and momentum towards the next conference – in Auckland, in partnership with Museums Aotearoa – became charged.

Of course these things don’t just happen and the Organising Committee spent many hours developing a program of formal and informal opportunities for exchange. It was my first involvement in this process and I came away thinking that a more curated and outcome focused program development might prove a better way of involving the broad church of interests MA seeks to represent.