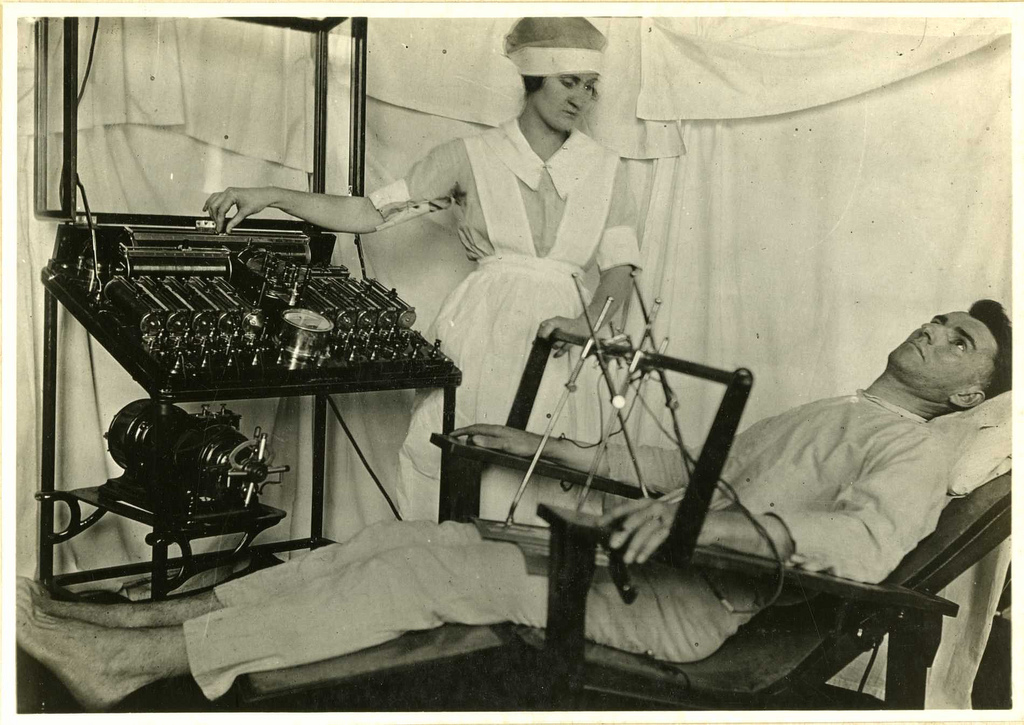

A Bergonic chair for giving general electric treatment for psychological effect, in psycho-neurotic cases

Caption taken from original photo description. World War I era. Photo: courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

Of all the museum themes, those that deal with human suffering in all its manifestations have enduring popularity.

Medical museums fall into this category and in taking a closer look at the public’s particular penchant for pathological tissue, contagious disease and antiquated medical equipment there’s much more than morbid attraction and medical voyeurism.

Medical museums come in several varieties. There are those occupying historical sites whose stories unfold over time and where hospital or infirmary history can be read as a chapter in a broader history. These are among the most accessible as they can be interpreted through the microscope of our social history. We’ve featured some of the museums in this category in our Sick in the city Trail.

The public’s particular penchant for pathological tissue, contagious disease and antiquated medical equipment reveal much more than morbid attraction and medical voyeurism.

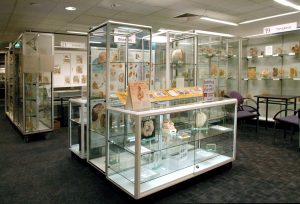

Then there are medical museums that wind the microscope in much, much tighter to focus on disease and its treatment in minute detail. Collections in museums such as the Museum of Human Disease and SPASM (Society for Preservation of the Artefacts of Surgery & Medicine) mostly originate from within universities or have evolved through a profession’s documentation of itself. Diseased organs, tumours and abnormal physiology were harvested and preserved for teaching purposes and kept alongside records of treatment procedures, patient records, photographs and doctors reports.

Visiting these museums can evoke a visceral response – fear of illness and memory of debilitating conditions can bring grief to the surface, casting the viewer back to a time when medical intervention was more invasive, painful and often ineffective. For some, this personal discomfort gives way to cathartic relief. This is especially relevant for families where psychiatric illness has wreaked havoc – knowing the history of treatment sometimes reassures and calms those affected by ongoing trauma. Documented stories of childhood diseases such as scarlet fever, measles and polio can provide strange comfort to those with direct memory of segregation, long convalescences and permanent impairment.

In NSW, we have several exceptional Nursing museums. From working class roots, to women’s suffrage and onwards, nursing is intertwined with the gendered history of the country, when nursing and teaching were the only two respectable professions available to an unmarried woman.

Medical museums or small museums with medical collections also tell stories about the important role the local GP played in the health and survival of a community. The removal of tonsils, the suturing of wounds and the setting of broken limbs often feature in these collections. Such stories are life affirming and serve to bolster our faith in medical technologies, revealing how improved health care is an important pillar of a civilised society.

So when you next want to get down and dirty with life consider a visit to one of our medical museums.