In September, the touring exhibition Aztecs comes to the Australian Museum. M&G was lucky enough to see this at Museum Victoria, braving a classic rain-swept, chilly Melburnian day and throngs of families. It was well worth the trip.

If you’re like us and have difficulty separating your Incas and Mayans from your Aztecs then here’s a quick rundown.

The Maya was the first Mesoamerican civilization, starting around 2600 B.C. They lasted the longest and, thanks to Hollywood, are most famous for predicting the world would end in 2012.

The Inca civilization can be traced back to about A.D. 1200. They lived in the mountains of Peru, and at the peak of their power the civilization of 16 million extended for 4,000 kilometers.

The Aztecs are the youngest, founding the city Tenochtitlan upon raised islets in Lake Texcoco in the Valley of Mexico in A.D. 1325. Among their many advances, the Aztecs used a 365-day calendar, played a unique sport called Ullamaliztlithat involved carrying a heavy ball between their knees, had universal education for children, and an advanced system of agriculture.

But let’s face it, we aren’t here to learn about farming or Mexican sport; we’re here for human sacrifice!

Many ancient cultures have bloodthirsty gods who need some sort of death payment, but the Aztec gods were particularly demanding.

Many ancient cultures have bloodthirsty gods who need some sort of death payment–the ‘nicer’ ones are happy with domestic animals–but the Aztec gods were particularly demanding. According to the Aztecs’ own records, they sacrificed about 80,400 prisoners over the course of four days for the re-consecration of the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan in 1487. Most people would agree, even for angry gods, this is excessive.

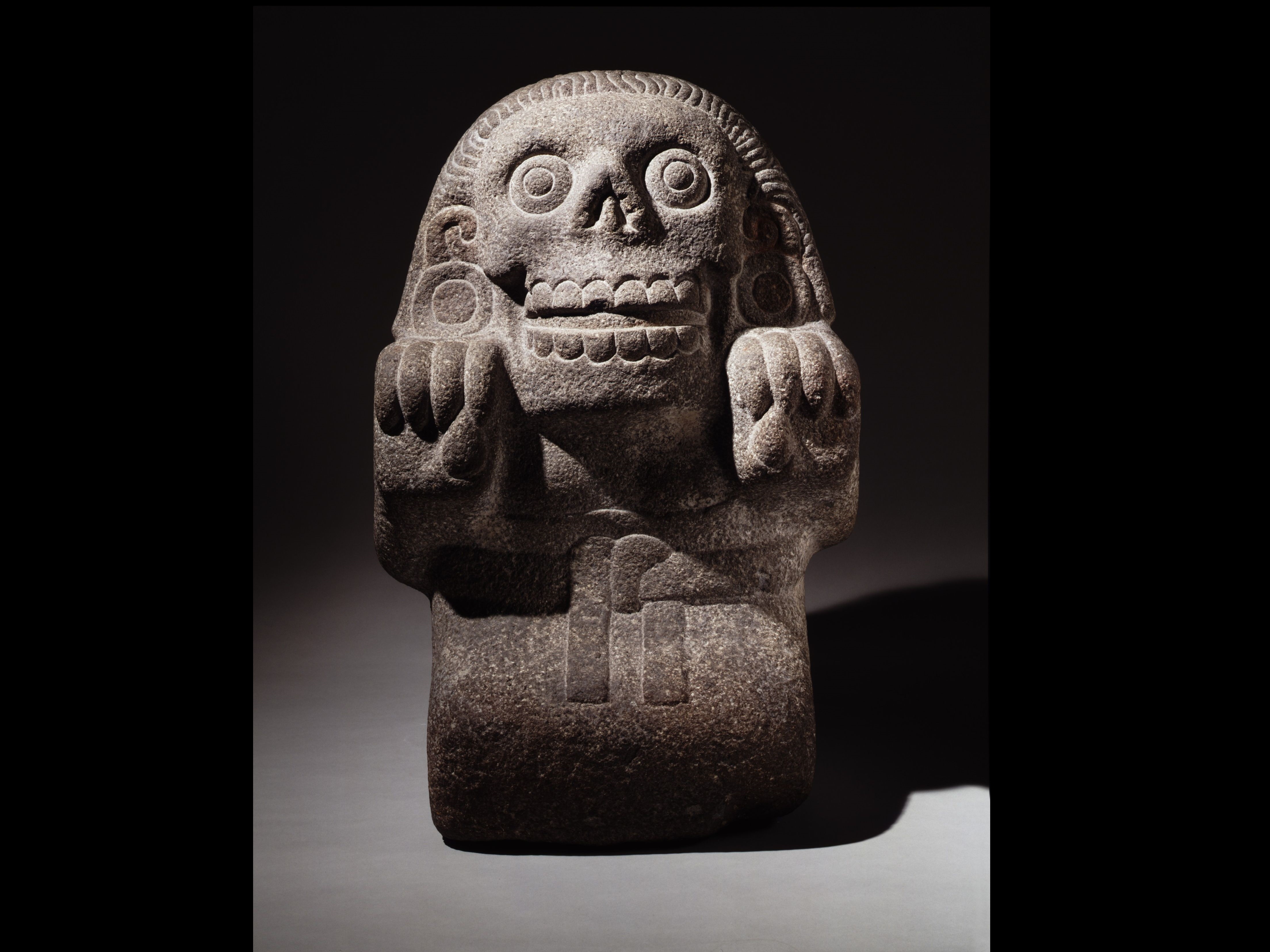

The exhibition designers of Aztecs knew exactly what we wanted. Aside from the beautiful models of Aztec irrigation, stone effigies of numerous Gods with bird heads, pride of place is reserved for the massive model of a temple. All around the temple are the objects associated with killing: the stone slab the four priests laid the sacrifice over: the ceremonial flint knives used to slice his or her abdomen open so they can get into the victim’s diaphragm: and the bowl held by a statue of the honored god, where the beating heart was placed.

Presbyterianism never looked so good.

All around the model temple are displays explaining the elaborate cosmology behind sacrifice. The Aztecs removed the heart (tona) because it was supposedly the seat of the individual and a fragment of the Sun’s heat (istli). They also believed the way people died determined the type of afterlife they experienced. The Aztecs meticulously organised death into several types, and these categories defined the ‘heavenly’ and ‘underworld’ levels the dead traversed. Passing away quietly at home required the soul to undergo a torturous journey, only to culminate in a dull underworld. ‘A good death’ was sacrifice, war or death during childbirth.

Our other fascination with the Aztecs is their untimely demise. The Spaniards conquered the Incans and the Aztecs, but the latter’s disastrous collapse is one of the great cautionary tales of the ill effects of unnecessary capitulation. The Aztec civilization was built on trade and tribute backed up by an effective military. For some reason, rather than fighting the Spanish outright, their leader Montezuma II, chose to give the Spaniards gold and host them at Tenochtitlan. Inevitably relations worsened until hostilities broke out leading to the massacre in the main temple and Montezuma taken hostage. The exhibition looks at some of the rationalisations about the leader’s actions (mostly around superstition). It also does a wonderful job of showing off the surviving legacy of this short-lived, highly advanced and slightly terrifying civilization in the living culture of Mexico.

Aztecs may not sound it, but its fun for all the family, especially if the family digs human sacrifice. Opens 13 September at the Australian Museum. Get a taste here

Aztecs was developed by the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in partnership with Mexico’s National Council for Culture and the Arts and the National Institute of Anthropology and History (CONACULTA-INAH), along with the Australian Museum and Museum Victoria.